‘Artists always get a carte blanche’. The anonymous curator of Meduza’s anniversary exhibition on the show’s origins, history’s echoes, and the role of art in times of crisis

Manage episode 491160059 series 3381925

From April 26 to July 6, the Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien art space in Berlin is hosting “No,” an exhibition marking Meduza’s 10th anniversary. Featuring works by artists from across the globe, the show invites visitors to reflect on the upheavals of the past decade — from war and the rise of authoritarianism to the deepening crises of polarization and loneliness. To learn how the exhibition took shape and what role art can play in moments of collective crisis, Meduza spoke with one of its three curators (the other two are Meduza founders Galina Timchenko and Ivan Kolpakov). This curator remains anonymous for security reasons. Below is a summary of the conversation.

It’s been over 10 years since Meduza set up shop in Latvia and began providing independent journalism to Russian-speaking readers. In that time, we’ve covered major stories — political crises, wars, corruption, natural disasters — alongside more cultural ones, like social trends, books, films, and music. Over the years, the Kremlin has repeatedly destroyed our business model, targeted our journalists, outlawed our work, blocked our website, and launched wave after wave of cyberattacks against us. And yet, we’re still here — and marking this anniversary felt important.

But with many of the crises we’ve reported on only deepening, a traditional celebration didn’t feel right. Fortunately, around the beginning of 2024, Meduza editor-in-chief Ivan Kolpakov came up with an alternative: an exhibition to help people reflect on and process the turmoil of the past decade.

When he approached a professional curator (anonymous for security reasons) with the “crazy” idea, Kolpakov was cautious at first — but the curator felt the idea made perfect sense. Meduza co-founder Galina Timchenko agreed.

The team began by creating an Excel spreadsheet, populating it with headlines from each week’s major events over the past 10 years — no small task. While Meduza’s English-language edition focuses on Russia (and, to a lesser extent, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe), the Russian-language edition — the largest independent Russian outlet — covers global news. For this reason, the result was a sweeping array of topics: war, climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, the rise of right-wing populism, migration, and much more.

‘No’ in photos

The process of distilling meaning out of all of this data was done manually — no AI involved, the curator stressed. “At some point, my apartment looked like the movies where they have those people investigating something,” they said. “You know — red lines and dots and images on the walls. I had these big A1 pieces of paper and sticky notes — and I was just sitting, going through this Excel [sheet] and writing down things that seemed important.”

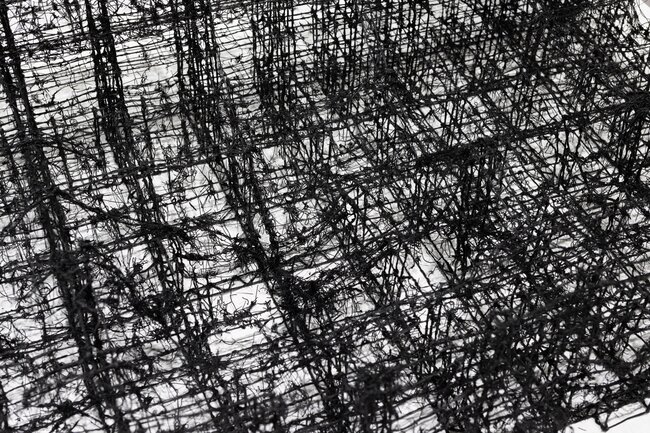

Eventually, the team distilled the decade into nine themes: dictatorship, censorship, exile, war, resilience, fear, loneliness, polarization, and hope. These became the names of the rooms that make up the “No” exhibition in Berlin. Artists from Russia, Finland, Turkey, Spain, Latvia, Chile, and beyond were invited to reflect on them.

Despite the wide range of topics and artists, the curator said it wasn’t especially hard to build a coherent show. What was daunting, they told Meduza, was ensuring the exhibition wasn’t “utterly depressing.”

"At some points, I thought, ‘Oh my God, why are we doing this to our viewers?’” the curator said. “Because analyzing this decade is really, really hard — this is the decade where the world has literally started to fall apart again.”

The world fell apart for our parents, our grandparents, and our great-grandparents… But I grew up being absolutely sure that everyone already understood that killing people is wrong. That civic freedom is what we’re all fighting for. That freedom of speech is a universal value.

The exhibition, which opened in April 2025, is far from depressing, though it does tackle dark and difficult topics. It’s dedicated to “those who have the courage to resist” — but this isn’t the only reason for its title, “No.”

“We’d been circling around this idea of a 10-year anniversary,” the curator explained. “And then all of a sudden, it turned out that the word ‘ten’ is the inversion of the word ‘nyet’ [нет] in Russian.”

Though largely based on the experience of journalists, the exhibition aims to speak to everyone. “The whole idea was that you don’t need to be a journalist to reflect on the show and to find something that speaks to you,” the curator said. “You don't need to be Russian to be able to perceive the show. And you don't need to be German, you don't need to be straight or gay, you don't need to be Black or White. You need to be just a human being.”

Flipping the script

Meduza’s Code of Conduct includes a section on objectivity and impartiality; journalists should “strive to report the news, not become the news.” One of the challenges in creating the exhibition was staying true to this principle while incorporating the experiences of Meduza’s journalists, who have been deeply affected by all nine of the exhibition’s themes.

To navigate this, the team enlisted exiled playwright Mikhail Durnenkov to interview Meduza journalists and turn their testimonies into a video installation.

“The presence of Mikhail, who’s also a specialist in documentary theater, allowed everyone to really feel comfortable,” the curator said. “It wasn’t like sharing your thoughts with [editor-in-chief] Ivan [Kolpakov], with whom the journalists have a working relationship. Instead, it was a neutral, artistic figure.”

When dealing with life-and-death issues like war, dictatorship, and exile, an art exhibition might not seem like the obvious response — as opposed to, say, a new fundraising drive. But the curator believes art is precisely what’s needed to reckon with this trauma.

One reason for this, the curator said, is that there’s a key difference between the way journalists and artists work: time.

“In the media, it’s chop-chop and it’s in the morning news,” the curator said. “With the pandemic, for example, a lot of really beautiful artistic outcomes are only coming out now. Because it takes time. Museum and exhibition work take time, because you're working with something very physical. But I think the most important role of art is to inspire its perceivers, its viewers.”

Artists, they added, don’t provide answers. “They raise questions, and viewers look for answers. And artists are free. Art is about instigating conversations and being critical about things that you don't like, be it right-wing or left-wing. And as a curator, that's my principle: artists always get a carte blanche.”

Bring the exhibition home

Loneliness and hope

One of the themes of “No,” loneliness, might seem less obvious than the others. But for the curator, its inclusion emerged from the past decade’s headlines as naturally as the others did.

“We, as humanity, have never lived so close together while being so distant,” they said. “Loneliness is hugely important. It’s about homophobia in Russia. LGBTQ+ people in Russia feel very lonely because they’re pushed into the closet, forced into hiding.”

And they’re not the only ones.

“Independent journalists still in Russia feel lonely,” the curator noted. “People with oppositional views feel lonely. People with mental health challenges around the world feel lonely. And people left alone with propaganda — any kind of propaganda — feel confused.”

When you can’t make sense of anything anymore, you start wondering, “Maybe what Trump says actually makes sense?” You’re so overwhelmed by information that you lose track of what can or can’t be said.

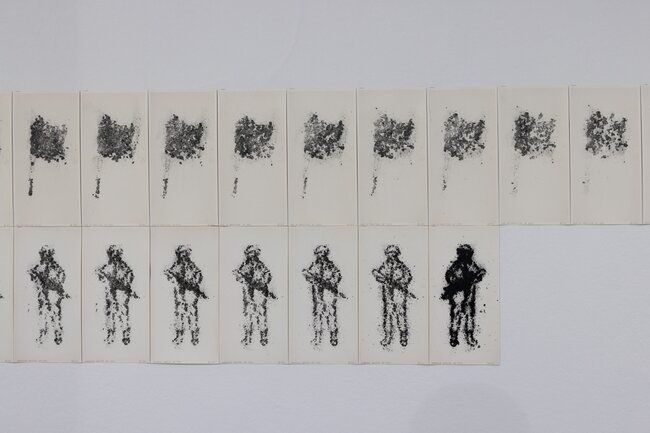

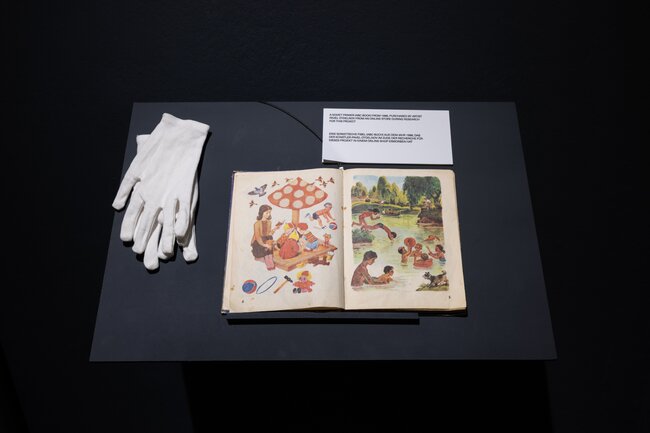

The “Loneliness” section includes work by Pavel Otdelnov and Alexander Gronsky. Otdelnov’s piece is a Soviet-style children’s alphabet book in which each letter stands for a different concept that he believes helped shape the worldviews of Soviet and post-Soviet people — from Radiation to Lenin. The work explores the loneliness that can come from being inundated with propaganda from early in life.

Gronsky approaches the theme from a different angle. A photographer — and the only artist in the exhibition still living in Russia — he documents how propaganda is seeping into Russia’s physical landscape.

“When you’re lonely in Russia, you can't express your views,” the curator said, paraphrasing Gronsky’s own statement about his work’s value. “And then someone says, ‘I like Alexander Gronsky photographs.’ And someone replies, ‘Oh, I like them too.’ And you immediately understand [each other]. It's like a secret code that you two share.”

Spending time with these works and reflecting on the past decade, especially in Europe, it’s hard not to recall the upheavals of the 20th century as a whole — and in the Exile room, especially its first decades.

“Of course, it feels like 1917,” the curator said. They noted that, as during the Russian Revolution, many Russian exiles today are going to cities like Paris and Berlin — especially artists. “So of course people think about [the parallels],” they said. “I’ve been thinking about it ever since the [full-scale] war began. Now I have more friends in Europe than in Russia — because nearly everyone I know has left.”

Another room that stands out is the last one of the exhibition: Hope. It features reflections from Meduza staff on why they continue their work despite the enormous challenges.

“Because it looks like a pretty hopeless initiative right now,” the curator said. “Even with the war ongoing, with exile, with news avoidance — it’s a very emotional, moving video. We’re not giving answers. We’re encouraging viewers to search for their own.”

The room also includes a piece by Alexey Dubinsky, a Russian artist based in Tbilisi, who painted the long lines of people waiting at Moscow’s Borisovskoye Cemetery for Alexey Navalny’s funeral.

“These lines were called Queues of Hope,” the curator said. “It was the last peaceful political protest still possible, in March 2024. And the number of people who showed up — that brought real hope.”

Interview by Sam Breazeale

64 episodes