‘Let’s stop feeding the bear’ . In Latvia’s easternmost region, ordinary people navigate growing militarization and a stagnant economy as the border with Russia hardens

Manage episode 480773863 series 3381925

Last month, Latvian authorities introduced increased restrictions at three border crossings, citing the risk of a “hybrid threat” from neighboring Russia and Belarus. One of Kyiv’s staunchest allies, Latvia has taken drastic steps to harden its borders since Moscow’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. And with the Kremlin reportedly expanding army bases and preparing to move more troops to its border regions along NATO’s eastern flank, Riga’s security concerns are unlikely to abate anytime soon. For residents of the Latgale region, however, the realities of cutting cross-border ties are complex to say the least. For The Beet, Rēzekne-based journalist Jack Styler reports on how the militarization of the border with Russia has affected ordinary people in Latvia’s easternmost region.

This story first appeared in The Beet, a monthly email dispatch from Meduza covering Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Sign up here to get the next issue delivered directly to your inbox.

The road leading out of the European Union is lined with port-a-potties on one side and an epic line of trucks on the other. Walking around the Terehova crossing in eastern Latvia, it’s clear that the infrastructure has been stretched to its limit to accommodate truckers waylaid at the border while moving European goods to Russia’s major cities.

Their license plates come from all over: Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Romania, Serbia, North Macedonia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Russia. Sunflower seed shells, empty liquor bottles, cigarette butts, trash, and — despite the portable toilets — human feces line the roadside, especially during the border’s busiest times. Like just before New Year’s, when many haulers rush to fulfill orders before the year’s end.

Crossing the border at Terehova was never hassle-free, but it’s become considerably more difficult since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. In response to the war, all three Baltic countries shut down land border crossings with Russia and Belarus. Terehova is now one of only two open crossings from Latvia into Russia — and it’s the most direct route for truckers from Europe heading to Moscow or onwards to Central Asia. And because of E.U. sanctions, Latvian customs agents closely inspect every Russia-bound truck.

Lieutenant Colonel Juris Mazūrs, the deputy head of administration at the Terehova crossing, says they’re working as fast as they can to process some 200 trucks per day, alternating between vehicles carrying refrigerated or fresh produce and those with non-perishable goods. Still, the line of trucks can number as many as 2,000.

When I first started interviewing truck drivers at Terehova last October, wait times could last as long as three weeks. Alik, a young trucker from Uzbekistan, said he had been waiting at the border for 10 days with his shipment of cookies and chips. A Latvian driver named Alexander, who was hauling alcoholic beverages to Moscow, said he had been waiting for seven days. When asked how he passed the time, he replied, “I walk back and forth, breathe the air, and read. I try to diversify my leisure time somehow, not sitting in the car all the time.”

Once, I saw a trucker preparing meat skewers on a portable grill balanced on his truck’s deck plate. Often, men carrying large plastic jugs would gather outside the bathroom of the Texas Saloon, waiting their turn to replenish their drinking water. One of two restaurants near the border, the Texas Saloon serves chicken soup, borscht, and other Eastern European staples. The décor vaguely adheres to the cowboy aesthetic, except for the Russian pop playing softly from the speakers. At the counter, where toilet paper and lighters are for sale, a waitress named Jolanta said she didn’t know how the restaurant got its theme.

“Every year it gets worse and worse,” said an older Latvian driver named Margots, who had been waiting for 12 days. “Everything’s bad,” said Ruslan, a trucker from Belarus. “We have to restore things so that all countries work [together] as they used to. And we have to trade everything. We have to be friends,” he added, before walking off.

A short, middle-aged trucker from North Macedonia named Jovan conveyed the prevailing sense of frustration most clearly: “Politics is getting in my way,” he said. “I’m interested in work. Good people live there,” he continued, gesturing towards the Russian side of the border. “And very good people live here.”

Jovan said he owns three companies: a fruit distributor, a transport company, and a side hustle buying clothing in Greece to sell in his native Macedonia. The wait times at the Latvia–Russia border had clearly started to get under his skin. He waxed poetic about how, during Soviet times, there had been set trucking routes with established overnight stops where a driver was entitled to a hotel room with a shower and everything else he might need. In the November cold, he wondered what he’d do when the Latvian winter set in. “I don’t know how much money I’m going to be paid,” Jovan complained. “It’s a dog’s life.”

‘Contact zone’

Since Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Latvia has emerged as one of Kyiv’s most stalwart allies and taken drastic action to harden its own border with Russia. Under President Edgars Rinkēvičs, Latvia’s defense budget will increase to four percent of GDP next year and then ramp up to five percent. Yet despite the national government’s staunchly pro-Western outlook, the reality of cutting ties with Russia has been awkward and difficult for many working people in Latgale, the country’s easternmost region.

Both the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Russian Empire governed Latgale for longer and with more direct control than the rest of modern-day Latvia, leaving considerable Polish and Russian influence on the region. As a result, Latgale has a distinct history and culture that’s still evident in the region’s demographic make-up and political leanings. In fact, Russian, Belarusian, Polish, Ukrainian, and other minorities combined outnumber ethnic Latvians in the region.

According to 2022 Latvian government survey data, approximately 55 percent of people in Latgale speak Russian at home, which is by far the highest of any region in Latvia outside of Riga. (In a 2012 referendum on adopting Russian as Latvia’s second national language, Latgale was the only region that voted yes, 56 to 44 percent.)

That said, many locals tie their identity not only to the nation as a whole but specifically to the Latgale region, identifying as both ethnically Latvian and Latgalian. According to Henrihs Soms, an associate professor of history at the Latgale Region Research Institute at Daugavpils University, Latgalian identity is predicated on two things: speaking Latgalian, a language closely related to Latvian that has at least 100,000 speakers, and practicing Catholicism, which the Polish introduced.

Historically, Latgale has also trailed behind the rest of the country economically. Today, it’s not only the least wealthy region in Latvia but one of the poorest in all of Europe. The unemployment rate hovers around 11 percent, which is over twice as high as in Riga, and workers in Latgale earn, on average, 35 percent less than those in the capital. (In 2017, a local journalist told Politico, “I suppose you could say that we are the Appalachians of Latvia.”)

Given its socio-economic differences and proximity to both Russia and Belarus, security analysts and Western media have long viewed Latgale as a potential flashpoint. Following the Russian takeover of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine’s Donbas region in 2014, which heightened concerns that Moscow might seek to destabilize the Baltic countries, Latvian police investigated a map circulating online showing an independent “Latgalian People’s Republic” split off from the rest of Latvia. Though locals had already expressed resentment over being stereotyped as a potential “fifth column,” this fringe RuNet idea still found its way into Western security analysis.

READ MORE FROM THE BEET

In 2016, the BBC provoked controversy by releasing World War Three: Inside the War Room, a dramatized hypothetical invasion scenario in which Russia leveraged the Latgalian identity as a pretense to start a pro-Kremlin “separatist rebellion.” According to Soms, however, rather than serving as a source of conflict, Latgale has historically been a “contact zone” between Baltic and Slavic peoples, where locals have a reputation for tolerance. “We always say that compared to the rest of Latvia, residents of Latgale are more open,” he said.

Be that as it may, the Russia–Ukraine war has highlighted differences of opinion in the region. According to 2024 polling data, only 38 percent of respondents in Latgale blamed Russia for the war in Ukraine, a significantly lower number than any other part of the country. This past fall, Latvian police investigated multiple locations where the Russian pro-war “Z” symbol was spray-painted around the region.

Though Daugavpils is the most populous city in Latgale (and the second-most populous in the country), the region’s real cultural center is Rēzekne, a smaller post-industrial city 50 kilometers (30 miles) from the Russian border. Known as “the Heart of Latgale,” Rēzekne reflects the region’s ethnic diversity. Historically home to significant Latvian, Russian, Belarusian, Polish, and — before the Holocaust — Jewish populations, the city’s population today is split nearly 50/50 between Latvian and Russian speakers.

Emblematic of the region writ large, Rēzekne boomed during the last century as a connection point between Europe and Russia. Built during the Russian Empire, two train lines connecting Warsaw to St. Petersburg and Ventspils to Moscow ran through the city. However, the routes leading to Russia shut down during the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, and there are no plans to restart service.

‘Riga is not Latvia’

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, daily life in Latgale reflected the region’s diversity and transitory history. Academics in Latgale and neighboring Belarus maintained close research ties. Locals would often cross over to Belarus or Russia to buy cheap gasoline. Some even worked jobs in Russia while living on the Latvian side of the border. On New Year’s Eve, in Russian-heavy pockets of Latgale, locals set off fireworks at 11:00 p.m. to coordinate with celebrations in Moscow’s time zone.

But the war super-charged the region’s pivot away from its eastern and southern neighbors. The once semi-permeable border has hardened completely over the past three years, and cross-border traffic has sharply declined, according to the Latvian State Border Guard’s data. Having built a 145-kilometer (90-mile) fence along the southern border with Belarus, Latvian authorities have nearly completed another 283-kilometer (176-mile) fence along the border with Russia.

READ MORE FROM THE BEET

The threat of a hot war breaking out in the Baltics seems higher now. Latvian President Edgars Rinkēvičs told Semafor last year that he believes Russia has been waging a hybrid war in the region since 2018, conducting cyberattacks, orchestrating arsons, and cutting undersea cables with its shadow fleet in the Baltic Sea. Danish intelligence services predict that Russia could move against Europe within the next five years. In mid-April, Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service chief, Sergey Naryshkin, said that the Baltic countries and Poland would be the “first to suffer” if conflict were to break out between Russia and NATO.

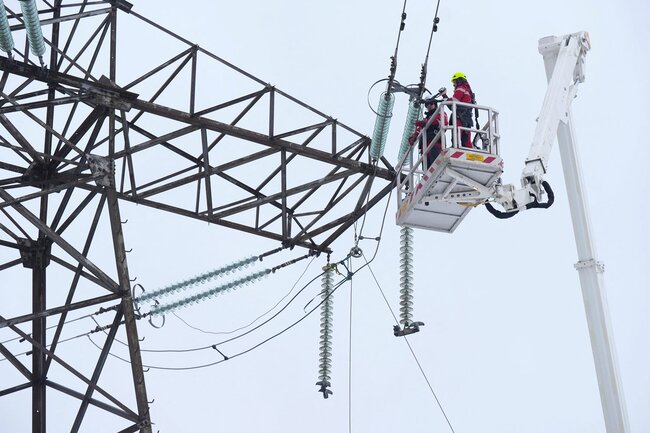

In response, Latvian authorities have prioritized ensuring the country’s sovereignty. NATO planes constantly patrol the “Baltic Defense Line” from the air, and the alliance recently launched a monitoring mission in the Baltic Sea. In February 2025, the leaders of the three Baltic countries — which stopped purchasing electricity from Russia in 2022 — met in person to “activate” their switch to the E.U. power grid.

In mid-April, the Latvian parliament officially voted to withdraw from the international convention banning antipersonnel mines, citing Russian aggression against Ukraine.

As their home has transformed from a “contact zone” to a potential front line, many living in Latgale have grappled with the prospect of war. Jānis Pampe, a new father who recently gave up his DJ gig at the local Latgalian-language radio station in favor of a job at an electric company, said his family has already decided what they would do if Russia were to invade Latgale. “We talked it out, and we will stay,” Jānis said. “Because where can I go, right? Show me a country that’s willing to receive three Latvians.”

Though he repeatedly condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and aggression in the wider region, Jānis pointed to a disconnect between the capital and the rest of the country. He kept repeating the same Latvian phrase, Rīga nav Latvija, or “Riga is not Latvia,” and expressed frustration over the idea that the only way to prove one’s “patriotism” is to take up arms. “I’m not a soldier, that’s not my job. Sorry, not sorry,” he said.

According to a 2024 survey, respondents in Latgale showed the lowest willingness to “fight for Latvia” if a war were to break out (26 percent). Living in Rēzekne, war is not an unimaginable scenario. A 2021 report from the D.C.-based Center for New American Security included a “fictional operation vignette” set in Rēzekne in 2030, in which local ethnic Russians start a protest for greater civil and language rights that turns into a riot fueled by Kremlin “agents provocateur.” Complete with a map of the city labeled with protesters, drones, Russian radio jammers, and NATO tanks, the story reads like fan fiction. (The U.S. “Charlie Company commander,” the anecdote’s heroine, works with a chewing-tobacco-addicted Latvian counterpart to “get these Russians out of Rēzekne.”)

Occasionally, military planes fly low over the city — so low, Jānis said, he can sometimes read the tail numbers. “That shit is scary.” As a new father, he’s up late most nights. Even though they are out of sight, “I hear the planes patrolling,” he said. “I hope they are our allies.”

‘Neighbors matter’

Jānis Igaunis runs a company in Rēzekne that makes log cabins and other eco-friendly structures. A native of Balvi, a town in Latgale’s north, he won the region’s “New Entrepreneur of the Year” award in 2021. But when asked how local business owners are navigating the current moment, Igaunis responded, “To be honest, I don’t quite feel like a successful business owner at this point, as my business is far from blooming.”

Even though Igaunis had no Russian clients before the war, Europe’s overall economic slowdown hit his business hard. “A big part of my products was holiday cabins,” he explained. “But if the economic situation goes down, [people] don’t buy yachts, holiday cabins, and campers.” Though he once employed 15 people, his team is now down to four.

Māris Andžāns, the director of the Riga-based Center for Geopolitical Studies and an associate professor at Riga Stradiņš University, assessed the situation in plain language: “It’s difficult when it comes to Latgale.” Though international organizations and consultants have looked at tourism, military production, and IT as potential sources of growth, “nothing has really worked so far,” Andžāns said. No new industry seems likely to make significant investments in the region, despite the creation of special economic zones (SEZs) that would give companies tax exemptions.

Regarding infrastructure, the Latgale region is the farthest from the capital, the country’s only international airport, and its major ports. “Russia and Belarus also matter significantly because that leaves a negative footprint on investment perception,” Andžāns added. “It’s obvious that the risks are higher in Latgale. Neighbors matter.”

READ MORE FROM THE BEET

Though “Latgale is going to be hit comparatively harder,” the economic decoupling has been a long time coming. As Andžāns explained, Russia has been building up its ports in the Gulf of Finland over the last couple of decades, directing more trade to the northern route instead of relying on intermediary states like Latvia. “It’s not going to come back — the same cargo and volumes — whatever happens,” Andžāns said.

Earlier this year, the Latvian parliament passed a 640-million-euro ($722-million) action plan to address the “worsening of the already unfavorable economic situation [and] difficulties in maintaining business activity” in the country’s borderlands since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. While Andžāns said the action plan was a positive step for the region, he doubted it would be a silver bullet.

“I sometimes have the feeling that people expect too much from the state,” Andžāns said. “Things are not going to be as they were.”

‘Patriots live here’

Rēzekne’s brand-new spa center features a large pool, hot tubs, and an assortment of saunas and steam rooms. But it has never had a single paying customer. Despite costing the city thousands of euros per month in heat and maintenance, the saunas sit empty and cold.

The spa center was the brainchild of former city council chair Aleksandrs Bartaševičs, part of his ambitious strategy to bring more money into the region.

Bartaševičs began his political career in the Latvian parliament, where he consistently advocated for the country’s Russian minority. First elected to the Rēzekne city council in 2009, Bartaševičs tied his political brand to ambitious construction projects. During his 14 years in power, Rēzekne built a concert hall, a youth center, a river promenade, and an Olympic sports facility featuring the only outdoor swimming pool in the Baltics. (It’s closed most of the year.)

Locals say the plan for the spa complex was simple: the city would build a state-of-the-art facility, a private contractor would construct an adjoining hotel, and tourists from across the Baltics, Russia, and Belarus would flock to Rēzekne. Construction began in 2018, and the city took out loans for the project, which ballooned in cost from 8 million to more than 12 million euros (the equivalent of $13.5 million today). Then, Russia invaded Ukraine. Construction of the spa center finished last year, but no investor has materialized to build the planned hotel. Maintenance and heat for the empty spa center currently costs the city 5,000 euros ($5,600) per month, according to Latvian Public Radio.

In 2024, the Latvian parliament voted to dissolve the Rēzekne city council for mismanaging municipal funds, effectively ousting Bartaševičs and his allies. Bartaševičs has also faced corruption allegations because a company belonging to his wife and brother received most of the city’s construction contracts during his tenure.

Since the mayor’s removal, an interim administration led by a Riga-based bureaucrat, Guna Puce, has implemented a crippling austerity plan to deal with the Rēzekne’s debts, which now total 115 million euros (about $130 million). Long-planned renovations to pothole-ridden main streets and plans to pave gravel side roads have been put on the back burner. Last November, the Baltic News Network reported that city officials worried they may be unable to keep up basic street-clearing services.

Nevertheless, Bartaševičs — who declined to be interviewed for this story — is running for city council in the June municipal elections. Just before he was officially removed from office, the former mayor told his supporters that the government in Riga has no love for either Rēzekne or Latgale. He is expected to win in June.

Construction projects aside, the local branch of Latvia’s Investment Development Agency (LIAA) has other plans for reinvigorating the region, including various initiatives to help local entrepreneurs looking to launch start-ups. Since 2016, the business incubator program, which gives out grants to entrepreneurs ranging from 26,000 to 50,000 euros (about $30,000 to $56,000) per year, has helped establish more than sixty small businesses in the region.

To qualify for the program, the start-ups can’t have ties to Russia or Belarus. But Skaidrīte Baltace, the head of LIAA’s Rēzekne office, says they haven’t run into any issues, since most applications from export businesses target markets in Scandinavia or mainland Europe. Their success rate, according to Baltace, has been high: the LIAA estimates that 80–90 percent of the business proposals they have accepted have developed into real enterprises.

READ MORE FROM THE BEET

It was a glimmer of hope in an otherwise bleak economic landscape. “Patriots of the country and the region live here,” said Baltace. “We live here, we work here, and we try to grow. We’re optimistic.”

* * *

Over the seven months I spent reporting this story, I kept in contact with Jovan, the Macedonian trucking company boss I first met at the Terehova border crossing. In late February, I asked if he would be coming back to Latvia any time soon. Jovan said it was possible, but at the moment, he was heading to Iraqi Kurdistan with a shipment of kiwis.

A couple of weeks later, Jovan informed me that everything had gone smoothly in Iraq and he was now on his way back to Skopje. I told him that the Terehova border crossing seemed to work faster now that the New Year’s rush was over. “There’s no work. That’s the problem,” he responded. “Previously, Russia bought [my] products. Now it produces for itself.”

Before the war, Jovan told me, he used to cross the border at Terehova more than 30 times per year — but he hadn’t been back in more than four months and had no plans to pass through Latvia. “Trump is smart and intelligent. Putin and Trump will decide for themselves,” he wrote. “Europe is fucked.”

In late March, a group of local businessmen and prominent members of Latgalian civil society organized a small protest calling for the complete closure of the border with Russia. They stood beside the road to the Terehova crossing point, holding signs that read, “Let’s stop feeding the bear,” as truck after truck passed by.

Hello, I’m Eilish Hart, the editor of The Beet. Thanks for taking the time to read our work! Our newsletter delivers underreported stories like this one to subscribers once a month. Like all of Meduza’s reporting, it’s free to read but relies on support from readers like you. Please consider donating to our crowdfunding campaign.

Story by Jack Styler for The Beet

Edited by Eilish Hart

64 episodes