The Moscow Metro’s strange ‘gift’ to passengers. How Russia’s world-class subway restored a life-sized wall sculpture of Joseph Stalin

Manage episode 483958003 series 3381925

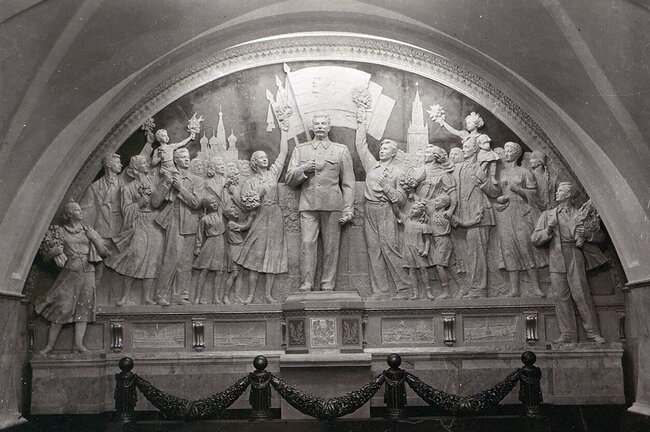

On May 15, a life-sized wall sculpture of Joseph Stalin was unveiled in the Moscow Metro. Subway officials described it as “a gift to passengers” to mark the transit system’s 90th anniversary. The following day, unidentified activists papered the installation with old quotes from Vladimir Putin and former President Dmitry Medvedev condemning Stalin’s repressions. The Moscow branch of the liberal political party Yabloko launched a petition against the sculpture. Elizaveta Likhacheva, former director of the Pushkin Museum, called it “amateurish work,” prompting accusations that she herself is helping to normalize Stalinist imagery. Meduza traces the history of this monument, from its 1950s origins to the present-day replica.

Typically, Moscow’s subway system eagerly publicizes any restoration work, but the Metro made an exception for the Stalin sculpture at Taganskaya station. Part of the passageway that hosts the installation was closed earlier this year behind a metal barrier and a sign declaring that “wall repairs” were underway. Most subway riders didn’t learn about the sculpture’s return until after it was unveiled.

As Novaya Gazeta reports, the first to bring flowers to the restored Stalin monument were members of Russia’s Communist Party, but their bouquets were soon joined by wreaths commemorating the victims of Stalinism. The day after the unveiling, unidentified activists posted quotations from Putin and Medvedev directly onto the monument. “That [Stalinist] period was marked not only by a cult of personality, but by mass crimes against the people,” Putin said in 2009. “Does Moscow’s Transportation Department agree with Vladimir Putin?” read an attached caption.

The artist behind the new wall sculpture is unknown, but speculation on the Telegram channels “MosGorDuma 2024 / State Duma 2026” and “Underground Restorer” suggests it could be architect Mikhail Matveev. These posts were later deleted, but Meduza obtained screenshots showing Matveev in a workshop with wall sculpture models. Nothing is known about the architect himself.

A one-of-a-kind original

Taganskaya Station opened on January 1, 1950. Like all stations on Moscow’s Circle Line, it was designed in the opulent late-Stalinist style. Lilac-hued marble lines the ground-level lobby, and the walls of the platform hall are lined with images of Soviet soldiers, banners, and military armor. Inscriptions read: “Glory to the hero sailors,” “Glory to the hero cavalrymen,” “Glory to the hero infantrymen,” and “Glory to the hero railwaymen.”

As architect Boris Rubanenko wrote in 1950, all this “leads up to the main feature: the wall sculpture at the end of the station that depicts Comrade Stalin.”

At the time of its unveiling, the composition was made of plaster, but by 1955, it had been replaced with a more durable version, crafted from white-and-gold majolica— a type of glazed ceramic. The monument was created by sculptors Yevgenia Blinova, who also worked on other reliefs at Taganskaya, and Pavel Balandin, best known as a sculptor of animals.

The panel’s original title was “Gratitude of the People to the Leader and Commander,” or “Stalin and the Youth.” Just like in today’s replica, Stalin stands amid a jubilant crowd on Red Square. In the background are St. Basil’s Cathedral and the Kremlin’s Spasskaya Tower. Below the scene are four plaques with images of cities that Stalin awarded the title of “Hero City” on May 1, 1945: Leningrad, Stalingrad, Sevastopol, and Odesa.

The majolica version featured several distinctive details: for instance, in the frame surrounding the panel, the plant motif was replaced with the coats of arms of the Soviet republics, and the background was no longer the light blue seen in the plaster version, but rather white and gold.

During the USSR’s de-Stalinization campaign, when depictions of the leader were being removed throughout the country, the sculpture was altered. According to books on Moscow Metro’s architecture, Stalin was removed from the Taganskaya monument in the late 1950s and replaced with either plaster coats of arms or a portrait of Lenin (Meduza found only textual descriptions, no photographs). The sculpture was renamed “Victory Salute on Red Square.”

In 1966, the panel was completely dismantled to make way for a transfer passage to the subway’s Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya line. It seems the original artwork was entirely lost.

A pale imitation

According to press releases from the Moscow Metro and the city’s Transportation Department, the current wall sculpture “exactly replicates the original.” But this is false.

Architecture researcher Alexander Zinoviev, one of the first to examine the restored monument, pointed out discrepancies:

While the general composition is preserved, the panel material (ceramic) is wrong; the color isn’t reproduced (neither the blue background of the plaster version nor the golden tones of the ceramic one). And the creators didn’t even try to replicate the ornamental details around the edge. The result is more of an ideological gesture than a true restoration of a historical architectural landmark.

Moscow historian Alexander Usoltsev has said he believes those behind the new sculpture “aren’t familiar with human anatomy”: “A person can’t stand like that. One of [Stalin’s] legs is shorter than the other.” He suggested that the subway system likely used “hobbyists,” not professional restoration artists.

Elizaveta Likhacheva, former director of the Museum of Architecture and the Pushkin Museum, also criticized what she described as “amateurish work”:

A real restoration would have required sculptors, molders, porcelain specialists, visits to [ceramic manufacturers in] Gzhel or Dulyovo, kiln work, and glazing. What was created in the 1950s wasn’t just Soviet art — it was porcelain sculpture, known as biscuit porcelain, and it was artistically and technically demanding.

What’s been installed in the Metro today is a shoddy 3D-printed plastic shell, crudely painted to imitate glazed porcelain. This isn’t art. It’s not even a reconstruction. It’s PR — a crude attempt to ride the wave of “patriotic hype” tied to yet another anniversary. No serious expert would support this.

The Moscow Metro hasn’t disclosed any details about the “restoration” work, including what technique was used to produce the new wall sculpture.

Some criticized Likhacheva’s remarks. For example, journalist Sergey Parkhomenko complained that Likhacheva would likely object to the restoration of the Soviet Gulag on artistic grounds before condemning the return of political prison camps. Alexander Baunov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin, argued that Likhacheva’s criticism of the new Stalin sculpture only “complicates and normalizes” the matter. On Facebook, he wrote:

Some in the architecture community want their outrage over the poor quality of a long-discredited leader’s image in the Metro to be read as bold defiance. And that’s exactly how it comes across — as a daring demand to imitate the leader’s image and style more meticulously, without cutting corners. It’s meant to appeal to today’s not-yet-discredited leaders.

Other reactions

The Moscow Metro and Transportation Department first announced the sculpture’s recreation on May 10. The next day, Alexander Davankov, a Moscow City Duma deputy from the New People party, criticized the idea, saying Stalin “remains a controversial figure” — a “symbol of [WWII] Victory” for some, but for others, the embodiment of “repression, fear, and shattered lives.” Davankov proposed putting the sculpture’s fate to a public vote, suggesting a plebiscite similar to the one Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin aborted in 2021 when considering the restoration of Lubyanka Square’s Felix Dzerzhinsky monument.

Five days later, the Stalin sculpture was unveiled at Taganskaya station, without any public discussion.

The Moscow branch of the Yabloko party has demanded that the Mayor’s Office abandon the restoration of the Stalin wall sculpture and has launched a petition against its installation. As of this article’s publication, only 1,456 people had signed.

Yabloko argues that it’s unacceptable to return “symbols associated with the darkest period of our country’s history” to the subway system. The monument, the party says, is “an affront to history,” “an insult to the descendants of Stalin’s victims,” and “a disgrace to the city of Moscow.” Yabloko also pointed out that Russia already has more than 100 installations honoring Joseph Stalin. In May 2025 alone, including the Taganskaya sculpture, three new Stalin monuments were unveiled.

The Communist Party, on the other hand, called the monument’s restoration “a reinstatement of historical justice” and expressed hope that more images of Stalin will be restored elsewhere across Moscow.

Yan Rachinsky, chairman of the historical and human rights organization International Memorial, wrote on May 15 that the sculpture wasn’t “lost” but dismantled by the Soviet authorities following the exposure of Stalin’s atrocities. It was in place for only 10 years and is therefore, in his view, “not historical, but anti-historical.” Rachinsky added that “the cult of personality echoes today’s propaganda,” which omits the victims of Stalin’s terror:

Among Stalin’s victims were more than 750 construction workers and employees of the Moscow Metro. More than 140 were executed, including the subway’s first director, Petrikovsky (his name appears in a Stalinist execution list dated August 20, 1938). There’s no mention of these people anywhere in the subway today, but the man responsible for their deaths is honored with a life-sized statue.

Dmitry Tugarinov, a Russian sculptor who created the Alexander Suvorov monument in Switzerland, noted that recreating such works requires “great care, to avoid sparking unnecessary controversy or associations”:

The Dzerzhinsky monument in Moscow was taken down with great fanfare, and now they want to bring it back. When people asked me about this, I said that removing the statue was stupid — and so is bringing it back.

Other subway Stalins

In the 1950s, references to Stalin were widespread in the Moscow Metro — not only in sculptural portraits, but also in mosaics and quotations. For example, the Avtozavodskaya Station was decorated with a poem by Kazakh bard Jambyl Jabayev praising the Soviet leader: “These are all the deeds born of Stalin’s wisdom.”

Several stations also bore the general secretary’s name: Semyonovskaya was known as Stalinskaya until 1961; Avtozavodskaya was called Stalin Plant until 1956; and Partizanskaya bore the name Stalin Izmailovsky Culture and Recreation Park from 1944 to 1947.

As noted by the authors of Hidden Urbanism, subway architecture researcher Alexander Zmeul and Moscow chief architect Sergey Kuznetsov, station interiors became increasingly luxurious in the later years of Stalin-era construction. This is particularly true of the stations built in what is known as the third phase, constructed during World War II; they effectively became the USSR’s “first monuments to the coming victory.”

Taganskaya, like the other stations on the Circle Line (then known as the “Great Circle”), opened during the fourth phase, built immediately after the war. According to Zmeul and Kuznetsov, this phase represents “the true apotheosis of Stalinist style,” and the decor is infused with “the theme of Soviet triumph”:

Stations built in the first half of the 1950s featured architecture that was no longer just palatial, but almost ecclesiastical, with ever-larger proportions and more extravagant decoration.

Historically, 10 of the 12 stations on Moscow’s Circle Line — all except Oktyabrskaya and Park Kultury — featured depictions of Stalin. These images were removed during the de-Stalinization period, which stretched from the mid-1950s to the late 1960s. With the subway, the campaign to dismantle Stalin’s cult of personality focused specifically on erasing references to Stalin himself, not the stations’ lavish design (though that, too, faced criticism under Khrushchev’s “elimination of architectural excess” initiative).

Officials removed statues, portraits, mosaics, medallions, and other items, replacing odes to Stalin with images of Lenin and celebrations of the Soviet victory over the Nazis. At Dobryninskaya Station, a portrait of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin supplanted Stalin’s painting. In other places, like Arbatskaya Station, an enormous Stalin portrait was simply plastered over.

In 2009, as part of restoration work on one of Kurskaya Station’s street-level entrances, a line from the Soviet anthem’s second verse — removed in 1961 for mentioning Stalin — was reinstated: “Stalin raised us to be loyal to the people.”

The restoration team said it had merely recreated the lobby to match its original appearance when it opened on January 1, 1950. However, the crew chose not to include the Stalin statue present at the station’s inauguration, saying that it “had not been preserved.”

The inclusion of Stalin’s name at Kurskaya drew objections from the Russian Orthodox Church, Moscow’s Cultural Heritage Department, and human rights activists. The group For Human Rights sent a letter to then-Mayor Yuri Luzhkov calling for the Stalin quote to come down. The renowned writer Boris Strugatsky was among those who signed the letter.

However, at the reopening ceremony, Dmitry Gaev, who headed the Moscow Metro at the time, said all the restoration work had been coordinated with the Mayor’s Office. Additionally, Alexander Kuzmin, then Moscow’s chief architect, stated that the Stalin line should remain:

If you take on a restoration, you need to recreate it as the artist originally intended. I’m no Stalinist, but I respect the work of those who came before me.

In the end, the protests changed nothing. A year later, there were similarly feeble complaints when the subway displayed archival photos of Stalin at several stations to mark the Metro’s 75th anniversary. Human rights activists at Memorial described the initiative as a “creeping rehabilitation of Stalinism.” Metro spokeswoman Svetlana Tsareva responded to the backlash by saying the image was “a historical photograph capturing the spirit of the era.” “By and large, our society is made up of rational, reasonable people who will understand this,” she explained.

Neither the Russian Orthodox Church nor Moscow’s Cultural Heritage Department has commented on the new Stalin sculpture at Taganskaya Station.

Story by Asya Zolnikov

Translation by Kevin Rothrock

68 episodes