‘We need more voices in the conversation’. Artist Pilvi Takala on Finland’s militarization and the role of art in a time of national crisis

Manage episode 490976980 series 3381925

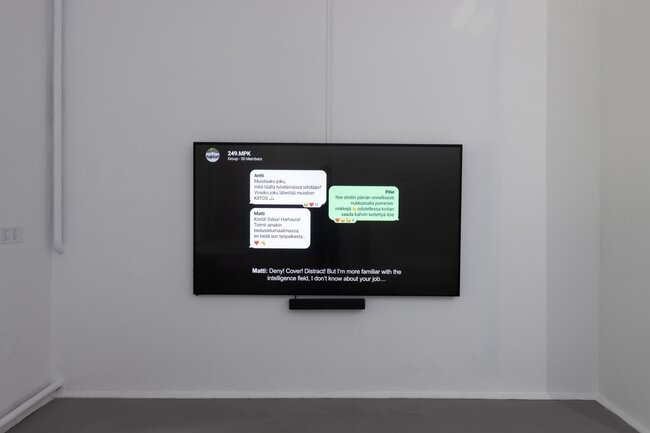

For more than 60 years, the Finnish military has operated the National Defence Course, an invitation-only program where influential members of society spend several weeks learning about the military and defense issues. While most participants are politicians, government officials, or business leaders, some spots are set aside for civil society members, including artists. One recent participant was multimedia artist Pilvi Takala, who created a video about the program for “No,” Meduza’s ongoing exhibition in Berlin. She spoke with Meduza about the experience and the complicated feelings it stirred in her about the relationship between art, society, and military threats. Below is a translation of the conversation, edited for length and clarity.

What is the National Defence Course?

It’s organized by the Finnish Defence Forces, the Finnish military. The idea is to invite people who have influential positions in society to come together and learn about defense and preparedness. In the early days, the participants were all men and were more strictly from certain fields, but over the years they’ve expanded. Nowadays, even people from creative fields and social media influencers are invited, and they strive to include more women.

They speak a lot in the course about how the participants are “a cross section of society,” which is true in the sense that many different fields are represented, including businesses central to defense and preparedness, the Defence Forces, education and culture, the media, NGOs, politicians, and government officials. But the defining factor is that everyone is high up in an org chart, apart from the occasional freelancer like myself. Everyone is in a position of power. So it’s an elite group — not so much “a cross section of society.”

The course has been very successful in defining itself as prestigious. People in high positions are often waiting for their invite to the four-week course for years, and they almost always make time away from their jobs to attend. It’s very rare to decline the invite. The course contents are largely confidential, including the list of participants, which adds to the feeling of importance.

The course is sort of like an adult summer camp, and building camaraderie among the 50 participants is as important, if not more important, than the content. Participants who are used to leadership positions and responsibility in their jobs get to spend four weeks in the care of the military; everything is organized and thought of for them. The course cohort keeps in touch afterwards, often for life, and there’s an option to join the alumni organization for the 10,000 people who have been through the course.

Like defense in general, the course enjoys a sort of “untouchable” status in our society. There is very little criticism of it in the public discourse. Also, the course is one way this unquestionable status of defense is fostered in Finland. The course is an effective lobbying tool for the Defence Forces: in 2015, it was named the Communication Initiative of the Year by The Finnish Association of Communication Professionals.

What specific activities do you have there?

Some of it is very school-like: you sit in a room and somebody gives a presentation about how a specific government organization works, and then there are questions afterwards.

Then there are visits to different locations, such as police facilities, the border guard, the hospital, a civil defense shelter, and different military bases. One of the trips to a base is always made on a military aircraft, with fighter jets escorting the plane. This “wow moment” was early in the course for us, and the group behaved like schoolkids on a class trip. Towards the end of the course, there is the main bonding event: a three-day sleepover at a military base, where everyone wears uniforms.

Throughout the course, we also worked on a scenario exercise together, including roleplay, where we formed ministries and were given a crisis scenario to respond to. On the surface, it’s about learning how the decision-making processes work in Finland at a time of crisis and experiencing the negotiations behind the hard decisions that have to be made. The roleplay also works as a teambuilding exercise and, more interestingly, as a way to normalize and diffuse the fact that there are many opposing political views represented in the room that might come in the way of bonding as a group.

What was your personal reaction to this experience?

I’m still doing the work of understanding and unpacking the experience. For me, it was a very uncomfortable setting. I felt really out of place. I hadn’t heard about this course before. I guess I don’t hang out in those circles.

I was both impressed and terrified by the way the course was constructed, the way it was designed to influence. While many of the more formal rituals and traditions in the course felt alienating to me, and didn’t really make me more committed, just going through the motions of the course certainly had an effect.

The whole experience is very intense — an exception to anyone’s everyday life. The days are long and you’re bombarded with information. There’s very little time to reflect. The issues covered are predominantly from a defense perspective, although there were also very interesting sessions on humanitarian organizations, culture, and national identity. Critical questions are encouraged, but there are rarely any proper responses to them, nor is there time for an actual conversation and reflection. Asking critical questions felt important in that context, though it also seemed like just a way to “include” critical voices, while not taking them seriously. So I often felt like I didn’t just want to fulfill the role I was assigned, as someone throwing in one critical angle at the end.

One of the questions that interested me was, what is my role as an artist there, beyond being a “critical voice,” or perhaps a clown? What are the expectations for an artist? Culture and art came up mostly in the context of protecting cultural heritage in crisis, taking the important paintings to a bunker. In one session, my coursemate asked a question that says something about the possible expectations: “How are we going to make artists make patriotic art, when they are all liberals?” I feel like my task as an artist is to work with issues that are difficult and tense. I don’t think this role will change in a crisis. There will be more difficulty and more tension and more need to find ways to work through those issues.

Were you allowed to film anything? What kind of art will you make based on your experience in the course?

I didn’t film there, but we were allowed to take photos, as long as we didn’t show certain areas or publish any photos where our coursemates could be identified. But we were also encouraged to take pictures of the military equipment, the planes and tanks, and to post those on social media. A lot of group pictures were taken and the course had a photographer documenting many of the activities. We got these photos at the end of the course, and I am using some of these images in my work.

My main way of documentation is usually a diary, and I took time after the long days in the course to keep a detailed one. I especially paid attention to the tension between the ways the course pulled me in and the ways it made me uncomfortable, because both things were happening at the same time. I’ve tried to understand the ways the course is designed to influence people, how the different aspects worked on me personally, and what kind of feelings came up.

To help myself understand the course better, I spoke to political scientist Johanna Vuorelma, who had been through the course before me. We spoke about how the different aspects of the course felt for us and in what way they were effective. For me, the way the course made me feel like a schoolkid was quite scary. While we were all aware of this and joked about it, after four weeks of a rigid schedule and little autonomy, a certain compliance arises.

Were people talking about the threat of war in Finland before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine?

It’s definitely been at a totally different level since the full-scale war in Ukraine started. At the same time, I think it’s always been there. If you look at the biggest media outlets, their language and what they’re talking about is very different now. Finland also joined NATO as fast as possible, without proper public debate. But Finnish society was already pretty militarized before, and military service is compulsory for men.

While I haven’t personally been so concerned with defense or national safety most of my life and haven’t done military service, I feel like it’s necessary to engage with the topic. It tends to be only men in uniform talking about this, and the discourse is very limited, while the role of defense and its budget are growing. It’s very hard to discuss, because the threat discourse erases everything else. The dominant narratives are “We don’t exist if we can’t defend against Russia” and “We have to prepare for everything possible.” This preparation will never be complete or perfect.

Obviously, we do need to prepare, but we should also think about other life-sustaining things, like healthcare or climate change [mitigation], for example. And we need more voices in this conversation. Because I don’t think, understandably, that anyone from the Defense Forces will ever say, “Now we have all we need for defense.” So we can’t just stick to the hierarchy of “defense first” — we need some balance.

Right now, it seems that anyone questioning defense spending or the military is on the side of the enemy. Either you are for Finland and don’t question defense, or you are a Russian spy or clueless hippie. A lot exists between these extremes, and those are the conversations that need to be happening more. It’s not sustainable for defense to be so exceptional and untouchable. Criticism is only healthy and actually makes any organization stronger. Art is one way to bring nuance to the conversation.

I’ve also been active in campaigning against Finland’s arms trade with Israel, particularly with a citizens’ initiative that proposes that human rights be considered when making defense purchases. Fifty-six thousand Finns who supported the initiative see that financing genocide and apartheid through arms purchases from Israel does not create national safety for Finland. This campaign was one way of empowering people to participate in the defense discourse and normalize that as a topic for anyone.

Meduza is a media outlet in exile. While most of our team is Russian, it includes people from Latvia and other countries, and we’re working with lots of artists from various countries for this exhibition. But still, for most people who see the “No” exhibition, it’s a Russian art show. Are you expecting any backlash for participating?

I don't expect any real problems. Once you mention that it’s media in exile, everybody thinks it’s okay. Since Finland’s main newspaper is also collaborating with Meduza, it's well-known and legitimized there. And I think we need more of these things.

Finland is going to be next to Russia forever. I understand that we don’t have diplomatic relations right now, but we can’t pretend that it’s not there, or that it’s only there as a threat. We need to learn to interact in a productive way. I don’t have an answer for what that would look like. Of course, there are more and more sanctions and other means of pressuring Russia as the war goes on, and I think there should be, but when it comes to art and culture, things are starting to change a bit. The Sibelius violin competition didn’t accept Russian participants in 2022, but this year they accepted Russians who condemn the war. So in the field of culture, there’s a shift towards not rejecting people just based on their origin.

There is still a lot of hate towards Russians in Finland of course. And there are many who categorically just reject anything Russian in any form, which I don’t think is a very healthy attitude, nor sustainable in the long run.

Meduza’s ‘No’ Exhibition

- Highlights from the opening ceremony of Meduza’s ‘No’ exhibition in Berlin

- ‘No’ — The Book Our guide to Meduza’s tenth anniversary exhibition in Berlin is on sale now

- A heart to bring home Spanish artist Fernando Sánchez Castillo has created the first Alexey Navalny monument — a pocket-sized tribute you can keep

- ‘Sorry, society doesn’t develop like this’ Stéphane Bauer, the director of Kunstraum Kreuzberg hosting Meduza’s ‘No’ exhibition, explains how he avoids becoming trapped in an art bubble

64 episodes