A heart to bring home. Spanish artist Fernando Sánchez Castillo has created the first Alexey Navalny monument — a pocket-sized tribute you can keep

Manage episode 484206579 series 3381925

At 4:00 p.m. on May 24, Spanish artist Fernando Sánchez Castillo will activate his Expanded Memorial for Alexey Navalny at Meduza’s “No” art exhibition in Berlin. Visitors will be able to take home a miniature figurine of the late opposition politician, in exchange for sharing their beliefs in a handwritten note. (You can visit the installation any time between May 24 and July 6 — but don’t wait too long, as the number of figurines is limited.) For Meduza, art critic Anton Khitrov, who edited the exhibition texts for “No,” explains this iteration of Sánchez Castillo’s project, who else it commemorates, and why a pocket-sized plastic monument might be more powerful than a giant bronze statue.

When and where: The activation with artist Fernando Sánchez Castillo will take place at 4:00 p.m. on May 24 at the Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien gallery in Berlin. Ilya Yashin — a friend and ally of Alexey Navalny — will be there as a special guest. Admission is free, and the installation will be on display as part of the “No” exhibition until July 6. Unfortunately, visiting in person is currently the only way to receive a Navalny figurine. If you’d like to attend the activation event, please register in advance.

On February 28, 2022 — just five days into Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine — Moscow’s New Tretyakov Gallery closed its “Diversity United” exhibition ahead of schedule. The decision came at the insistence of the show’s organizer, the Bonn-based Stiftung für Kunst und Kultur (Foundation for Art and Culture). Before arriving in Moscow, the exhibition had been shown in Berlin; afterward, it traveled on to Paris. The title and structure of the project suggested a united Europe, with Moscow as one of its centers. Reality told a different story. “Diversity United” became the last major international exhibition of contemporary art to take place in Russia.

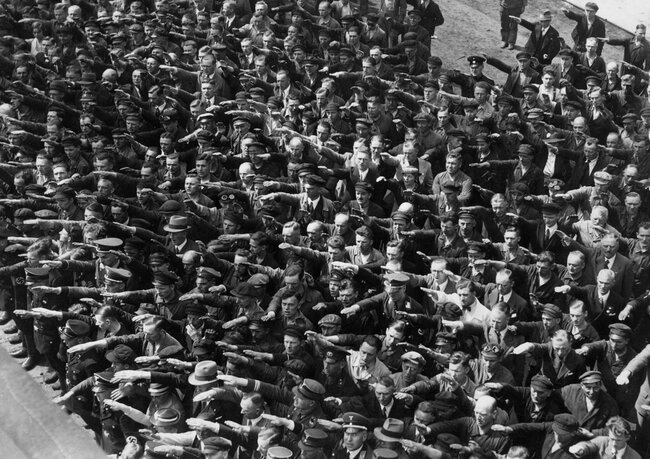

As a keepsake from the event, many visitors held on to a symbol of silent protest: a small plastic figurine of the German worker August Landmesser, the central figure in a famous photograph from Nazi Germany. In 1936, at a shipyard in Hamburg, a crowd raised their arms in the Nazi salute as a new military vessel was launched. Only Landmesser stood motionless, his arms crossed. His wife, Irma Eckler, was Jewish. Two years later, both were sent to concentration camps. Eckler died there. Landmesser was eventually released, only to be sent to the front. In the 1990s, their daughter Irene recognized him in the photograph.

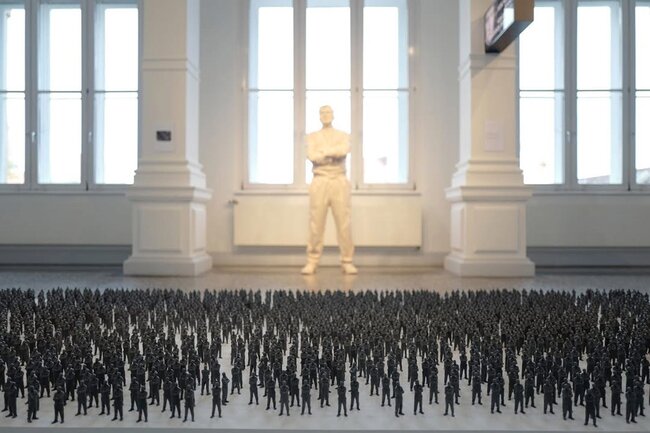

At the New Tretyakov Gallery, rows of Landmesser figurines were lined up on the floor — stocky, stern-faced, arms defiantly crossed — and given away for free. You could leave a message in exchange, but only if you wanted to. The project’s creator, Spanish artist Fernando Sánchez Castillo, invited visitors to write down any thought they wished and drop it into a ballot box — just like in an election. The author of this story wrote: “Freedom for Alexey Navalny.” At the time, the Vladimir Putin’s main opponent was already in prison.

Three years later, it turns out that at least four people connected to the “No” exhibition team brought their Landmesser figurines with them into exile. The title Sánchez Castillo gave the work — Expanded Memorial — proved exceptionally apt in this case.

Landmesser isn’t the only figure in Expanded Memorial. In different iterations of the project, Sánchez Castillo has offered viewers a variety of figurines. As a rule, they’re modeled on real individuals — peaceful protesters the artist has found in photographs. Often they’re anonymous, like the man on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square who, in June 1989, stood for several minutes in front of a column of tanks sent to suppress the protests. Or the student in Mexico City photographed during his arrest in October 1968, when the government violently cracked down on an anti-government student demonstration.

In an interview for the “No” exhibition catalog, Sánchez Castillo recalled how viewers in Mexico were hesitant to take the figurines home. In a country where disappearances remain a serious issue tied to organized crime, the “gaps” left in the installation’s neat rows struck many visitors as ominous.

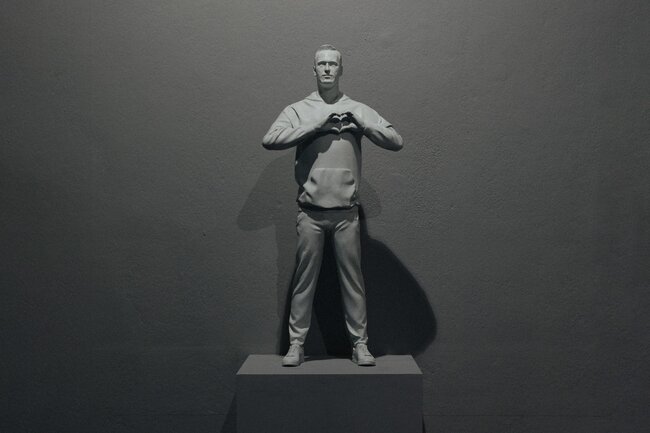

Alexey Navalny is an unusual subject for Sánchez Castillo. Most figures in Expanded Memorial commemorate events decades in the past. But, as the artist explains, he doesn’t have the luxury of waiting decades to create a tribute to Navalny. The sculpture on display in the “No” exhibition is based on a photograph taken on February 2, 2021, during the court hearing that sentenced Navalny to prison. That day, from behind the glass of the defendant’s box, Navalny looked at his wife Yulia and formed a heart with his hands. The now-iconic photo, which became the basis for the sculpture, was distributed by the Moscow City Court’s press service.

Like all sculptures in the Expanded Memorial project, the monument to Alexey Navalny exists in two versions. The larger one, cast in bronze and standing 90 centimeters (35 inches) tall, is a unique piece. The smaller version — a plastic figurine — was produced in 2,000 copies (with the possibility of additional runs). Both the full-size sculpture and its miniature replicas are on display in the Resilience room of the “No” exhibition.

Sánchez Castillo created Expanded Memorial in dialogue with traditional monuments. Public spaces — and the meanings that fill them — have long been central to his practice. In the 2000s, he devised a series called Protected Monuments: architectural models of Madrid’s historical landmarks as they appeared during the Spanish Civil War, covered for protection from bombs. Another work, Rainbow Seeker, is a fountain made from water cannons typically used by police to disperse demonstrations.

In European cities, monuments most often depict politicians or military figures; rarely do they commemorate peaceful protesters. Expanded Memorial is Sánchez Castillo’s attempt to shift that balance, if only slightly. But form matters just as much as subject. If a statue in a public square represents the presumed values of a community — or, more often, the declared values of those in power — then a figurine you take from a museum and place on your shelf reflects your own beliefs. Your neighbors may not share them. But they resonate with others who have taken home a piece of this “expanding memorial.” In a world where geography often no longer defines worldview, a network of monuments feels more fitting than a single immovable monument.

Once upon a time, it was common to decorate rooms with busts of great men (Eugene Onegin — an iconic character from 19th-century Russian literature — had a bust of Napoleon, for instance). Sánchez Castillo’s plastic figurines serve a similar function, though their style is entirely different. Because of their material and size, they more resemble collectible action figures of superheroes or pop culture icons. The artist himself sees them as toy soldiers in reverse: not glorifying violence, but peaceful protest; not submission, but freedom; not propagandized military valor, but civic dignity.

Still, the association with cheap plastic toys is hard to avoid — the figurines are mass-produced and identical. It could almost read as a commentary on the commercialization of protest, if not for one fundamental point: Sánchez Castillo gives them away for free. That alone makes his installation feel less like a display at a toy store and more like a political demonstration — and the figurines scattered chaotically across the platform resemble a protest crowd captured by a drone.

The Kremlin crushed Meduza’s business model and wiped out our ad revenue. We’ve been blocked and outlawed in Russia, where donating to us or even sharing our posts is a crime. But we’re still here — bringing independent journalism to millions of our readers inside Russia and around the world.

Meduza’s survival is under threat — again. Donald Trump’s foreign aid freeze has slashed funding for international groups backing press freedom. Meduza was hurt too. It’s yet another blow in our ongoing struggle to survive.

You could be our lifeline. Please, help Meduza survive with a small recurring donation.

People collect art at home for much the same reason they collect superhero figurines: it’s an attempt — sometimes an unconscious one — to answer the questions “Who am I?” and “What do I believe?” But art is rarely cheap. And it’s not always clear what a person’s collection says about them: Is it a reflection of their worldview, or just their financial means? Sánchez Castillo sidesteps that dilemma. You don’t own one of his figures because you paid for it — you own it because, one day, you took a slip of paper and wrote down what you believe. Or maybe you didn’t write anything and simply took the figurine — that’s fine, too. The artist doesn’t insist on a fair exchange. He prefers to leave the choice to you.

Sánchez Castillo’s project resonates with several other works in “No.” One of the exhibition’s key underlying themes is the normalization of war — the way the state and popular culture try to portray it as an exciting game, an adventure, or, in Putin’s words, a dvizhukha (a “bit of action”)

In her video work Feeling Defensive, Finnish artist Pilvi Takala recounts taking part in a multi-day training course run by the Finnish military. These events, meant to prepare civilians for crises like a potential invasion, resemble a kind of scout camp, and in a group chat, the graduates express nostalgia for the discipline they miss in civilian life.

The installation Where the Continents Meet by Turkish artist (and former political prisoner) Gülsün Karamustafa features camouflage uniforms in children’s sizes. In Turkey, as in Russia, children are dressed as soldiers for holidays. In Pavel Otdelnov’s Primer series, one illustration shows toy soldiers — the very kind that haunt the creator of Expanded Memorial.

At the same time, Sánchez Castillo’s critique of commercialized art (and, by extension, of capitalism itself) finds common ground with the Danish artist collective SUPERFLEX, who have long promoted the free circulation of ideas and imagery — and who live by that principle in their own work. At “No,” for example, beside their mural All Data To The People lies a stack of posters bearing the same slogan. Visitors are invited to take one home, free of charge.

Artists like SUPERFLEX and Sánchez Castillo are working to refine — or even redefine — the role of art. One such role, as suggested by their recent projects, is to build community. Visitors who leave with one of the Navalny figurines become, in effect, part of a network of like-minded people. In this way, Expanded Memorial not only restores justice by preserving the memory of those who fought for freedom — it also offers an antidote to loneliness.

Fernando Sánchez Castillo will activate his installation at 4:00 p.m. on May 24. If you’re in Berlin, don’t miss it! And be sure to check out the “No” exhibition’s other upcoming public events. On June 11 at Kunstraum Kreuzberg, Meduza’s publisher Galina Timchenko and journalist Polina Aronson will discuss how war and dictatorship affect our emotions; on June 22, we’re hosting a small book fair; and on June 25, there’ll be a speed-dating event — not for romance, but for finding new friends. You can learn more and register for the events here.

see the opening

Anton Khitrov

64 episodes